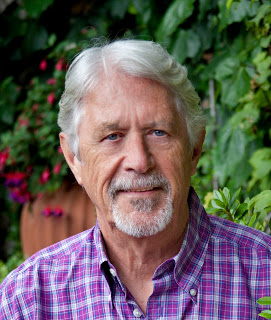

Guest post by Peter Clothier

(for my grandsons)

Tomorrow is your sixth birthday, Luka. In this morning’s meditation, my thoughts turned not only to you but also to my older grandson, your cousin, Joe; and to my own two grandfathers. I was thinking about how important grandfathers can be to their grandsons, and my own role as grandfather… I write down these thoughts for you both, so that you’ll have at least a passing acquaintance with your great-great grandfathers and your great-grandfathers, as well as with your Grandpa Peter.

Tomorrow is your sixth birthday, Luka. In this morning’s meditation, my thoughts turned not only to you but also to my older grandson, your cousin, Joe; and to my own two grandfathers. I was thinking about how important grandfathers can be to their grandsons, and my own role as grandfather… I write down these thoughts for you both, so that you’ll have at least a passing acquaintance with your great-great grandfathers and your great-grandfathers, as well as with your Grandpa Peter.

My father’s father, your great-great-grandfather, died of a heart attack on a business trip to New Zealand in 1938, when I was a year and a half old. My memories of him are for this reason second-hand, or through photographs. In only one of them, I think, are we seen together—with myself sitting on one of his knees and my sister, Flora, on the other. He is smiling with obvious grandfatherly pride. The other photograph I remember is the studio portrait of a still-youngish man in a stylish Edwardian suit and ascot tie, his eyes serious but gentle, with a twinkling suggestion of that mischievous quality about which I heard from my father. H.W. Clothier was considered an important, pioneering electrical engineer in his time; early in the twentieth century he invented a process called “oil-immersion switchgear” which made it possible for the first time for electricity to be used safely on an industrial scale. His only presence in my life was my father’s reverence for a man who died when he, my father, Harry, was still young himself. He would have been no more than thirty-two years old. I can only imagine how sad he must have felt. More of him in a moment.

My mother’s father, your other great-great grandfather on my side of the family, lived much longer. M (for Maurice) H. Ll. (for Llewellyn) Williams (a grand old Welsh name!) was a prominent minister in the Church of Wales—the Welsh cousin of the Church of England, the Anglican faith in which my father was also a minister (my mother grew up swearing she’d never marry one!) In his later years, after serving for a long time in a parish in Swansea in south Wales, “Grimp”—as his grandchildren called him—became Chancellor of Brecon Cathedral. As children we would visit him and my grandmother in the seaside village of Aberporth on the Cardigan Bay in west Wales, where they had a tiny, whitewashed cottage called Penparc. In my young eyes, Grimp was a sage, a man of inexhaustible knowledge and biting wit. I revered him, perhaps feared him a little, though he was gentle by nature, a pipe-smoker, a vegetable gardener, and a powerful swimmer: even in his eighties, at all times of year, he would be out for a long, steady swim across the bay over which their cottage windows looked. For some reason, I have a vivid memory of him at the breakfast table, chopping the head off a boiled egg.

These were my two grandfathers, your two great-great grandfathers, from whom I learned a lot, and both of whom I value even more as I grow older myself. Even in absence, my paternal grandfather remains a presence in my life, an elder statesman of great social and intellectual responsibility. From my maternal grandfather, who projected it, I learned a well-grounded sense of the power of the human spirit and a kind of inner peace that took me many years to discover in myself (even now, I’m not always very good at it! But getting better, I hope!)

So Harry Clothier was my father, your great-grandfather. Born in Newcastle on Tyne, he was the oldest of four siblings, who felt much of the responsibility for his younger brothers and sister on the death of his mother when he was only, I think, 13 years old. Her absence played an important part in his life, even though his father later remarried. He was educated at the renowned Shrewsbury School in Shropshire, England, and at Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge (where I also went; and maybe, one day, one of you!) After college, he decided he wanted to be an actor, then a monk (lucky for us, that he changed his mind!), and finally became a priest in the Church of England. He started out in the poorest, meanest coal-mining area of Newcastle, where he made no secret of the socialist views that he held for the rest of his life–and which I, your grandfather, inherited. Then he was ordered by his doctor to move south for his health–he suffered from severe stomach pains for much of his life–and was the parish priest in several small villages north of London: Aspley Guise, where I spent my days as a child, then Braughing, and later Sharnbrook. He and my grandmother, Peggy, bought a cottage in her grandparents’ village of Aberporth, where they spent their last years. His great hobby was carpentry and, later in life, when he discovered his skill with the lathe, creating wonderful bowls out of (mostly) dark, polished walnut wood.

And here we diverge: Joe, as you probably know, your other great-grandfather was Reginald (“Reg”) Foot, who was a native of the southwest of England but moved to the Channel Islands, between England and France, before World War II. At the start of the war, the Germans invaded the islands and forced all the non-native islanders to relocate in internment camps in Germany. While by no means the terrible concentration camps where so many were brutally murdered, in their internment camp the family lived imprisoned behind barbed wire–a dreadful circumstance for the health and well-being of any family. Your grandfather, a teacher, started a school for the youngsters in the camp–a service for which he was later in life honored by the Queen. After the war, he returned to Germany as headmaster of a British Forces school in Dortmund, which is where I came to know him as a gentle, thoughtful man, given to sometimes long periods of retreat when offended or angry. He drove a Citroen Déesse–a rather strange classic car that used to hiss up and down hydraulically when stopping and starting. And he had a huge, slobbery St. Bernard dog that he seemed to dearly love.

Luka, your other great-grandfather, your mother’s grandfather, and Grandma Ellie’s father, was a Hollywood screenwriter, a novelist, and something of a man about town! His name was Michael Blankfort. In his day he was President of the Writers’ Guild, a vice-President of the Academy and a Board Member of the Los Angeles County Museum. Quite an important person in the Los Angeles cultural world, then, and well known for his community work. In his young day in New York he was something of a social activist (rather like your other great-grandfather, Harry, over in Newcastle), dedicated, along with many of his friends, to socialist causes, defending the rights of workers and the poor. In the 1950s, when socialism in America was equated with the hated Communism, your great-grandfather was embroiled in a later much-discredited government “investigation” of movie actors, directors and writers, in an episode that cost him (and others!) many friends. He mourned their loss over many years, and never really reconciled. With his wife, Dorothy (“Dossy”) be became an avid collector of contemporary art, and many of the works in their collection, on their death, went to the County Museum. You can still see them there today–a great tribute to his sense of civic responsibility and his generosity. A gregarious, people-loving, passionate and loquacious man, he lived for his words, and loved nothing more than to preside over a long evening’s seder.

You both know your grandfather, perhaps not as well as I would like—especially you, Joe, who have lived so far away. It’s to my great and lasting regret that I have not been able to spend more time with you and your sisters, and to get to know you better than I do. You are now a young man, and even young men need grandfathers. You are lucky to have another one living closer than I do. Still, I relish just quite simply being a grandfather to two excellent grandsons!

What do you know about your Grandpa Peter? Well, you surely know that he is a writer—he makes a big deal out of that. It was not always the case. For many years, even knowing I was a writer, I worked as a teacher of language and literature at various universities; and later as an art school dean. I was fifty years old before I realized that, if I wanted to be a writer, I’d better get started! So for the past thirty years I have not had a “job,” in the real sense of the word. But I have been working. If I’m lucky, one day you’ll come across something I wrote—a novel, a book of poems or essays, a magazine article. But maybe not. Even after all this time, I’m certainly not a “famous” writer. But many people read what I write, and it means something to them, so that has to be enough.

More important than that, and better than that, is being your grandfather. Men, as you might—or might not!—find out as you grow older, have a more difficult time than women in connecting with their feelings, let alone expressing them. I was fortunate to find out about their importance some years ago, having been for many years disconnected. I now see them as co-equal with the intellect, the body, and for want of a better word, the spirit as representing the full integrity of a man. A four-poster tent–an integrated whole. So this is our integrity, as I see it, and it is our most important asset. To be fully in integrity means to be a man of your word: to always say what you mean, and mean what you say.

I have also learned, in my latter years, that it’s important not to hide, either from myself or from others. The downside of being a writer is that I spend a lot of time with myself, and while the Socratic axiom, “Know thyself” is a prerequisite for really knowing others, eventually it is others—like you two grandsons and, Joe, your sisters—who give my life its true purpose and meaning. I have come to believe that real happiness lies in the extent to which we are able to connect with and serve others in our lives, and my wish for you both is to find ways to accomplish that end.

I trust that you will always know how much your grandpa loves you, even when he’s not one hundred percent present to show it; and even when he’s sometimes not good at remembering to say it. I would wish it to be something to carry with you, as I have carried my own grandfathers with me, not exactly knowing them, but knowing they were there.

Select Page